Digital Poetics 3.29 On the Fly with Andy Robert by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

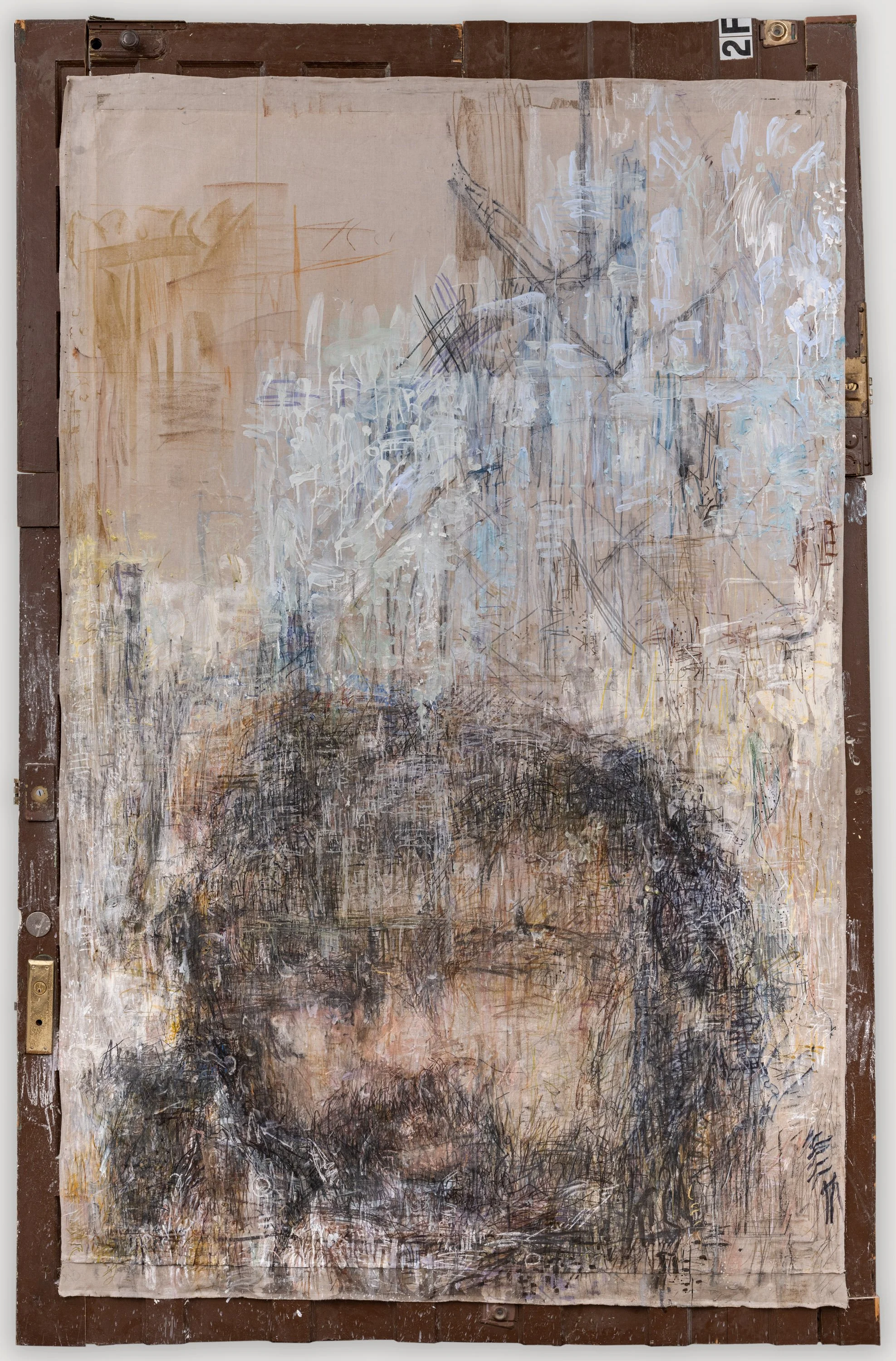

Andy Robert, “Tu Ca! Koté Ou Pralé, Ti Ca?”, 2022, Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles.

Birdsong and laughter are sounds that don’t mix. Beyond my window, I hear them both. There is the continuous call of a bird I can’t see or name, a scuffle of wing and claw. There is the deep cooing of a pigeon, the squawk of a gull, the sharp guttural caw of a crow. Beyond my window, beyond this avian body of sound, I imagine obsidian feathers, tar-stuck and jewelled, yellow beaks, prying eyes, round and peripheral. I imagine a chorus of wings spread outwards, horizontal, defensive, destructive, diaphanously strong. I imagine a feathered list in my bird book: members of the ‘Lari’, ‘Columbidae’, ‘Corvus’, winged throngs whose names contain places I, again, have never heard nor seen. I imagine lands formed into small bodies, small bodies gracing outstretched lands; sand and heat, rock and stone, moving through pin-pricked eyes, skimming salted oceans, soaring heights beyond my window, my bird book, my imagination, my wingless sense of time and place.

Laughter cuts in, cuts out my imaginings; laughter more raucous than a rook’s guffaw. Workmen have arrived, scaling the exoskeleton of scaffold, jeering, then complaining, about rain. The birds stop, sound suspended, take flight, find another roof to explore, their cawing a distant echo against brick and slate.

But I am imagining these echoes, calls and greetings, moving through sky and cloud apace, travelling to hotter climes and shores, only to come back-to me.

*

I type ‘Ti Zwazo’ into Google Translate, just to make sure I heard the gallery assistant correctly. The words ‘Little Bird’ appear in bold font, a confident confirmation to the loose and hesitant scrawl found in my notes. It gives me the option to hear ‘Little Bird’ in English and a cheerful feminine voice repeats the phrase through my speakers. There is ‘no voice output’ for Haitian Creole, the epithet’s original language. YouTube provides me with crow cries and pigeon purrs, dove love and gulls stealing chips, but only a Haitian nursery rhyme allows me to hear the entire phrase pronounced correctly – and fittingly in a sing-song, child-like peel of joy. I say it out loud to myself in my room, empty of any recorded joie de vivre, knowing full well that no matter how hard I try, my pronunciation is off. Another language lays light in the head but thick on my clumsy tongue.

‘Ti Zwazo’ forms part of the title of Andy Robert’s latest exhibition at the Michael Werner Gallery. Ti Zwazo Clarendon: You Can Go Home Again; You Just Can’t Stay is the full title to the show and speaks of the diminutive term’s great migration, the diasporic longing for ‘home’, the recreation of it elsewhere (Clarendon), the sense of never belonging to either place, whether you intend to ‘stay’ or not. (Little bird, Ti Zwazo, look how far you’ve come). From Haiti to Clarendon, New York; from New York to London, Robert comes to us, in full flight mode, on the fly, on the fly, occasionally going off-grid with changeable connotations and associations that flit in and out of sight across and under the surfaces of his layered paintings. Offering us clues, the occasional coordinate indicated by a word or phrase, Robert’s work forms a hazy cartography, one that maps movements and methods, moods and meanings, only a little bird – ‘Ti Zwazo’ – could fathom and follow.

That Robert does not translate the Haitian Creole phrases (of which ‘Ti Zwazo’ is just one) again demonstrates his reluctance to categorically fix his works. Like his roving and evolving brushstrokes, titles morph and mislead, persuading us to go in another critical direction, to jump over unsteady titular and conceptual thresholds, and land in the unknown. Refusing to be parsed, transcribed, glossed and standardised into one identifiable form or idea over another, Robert’s paintings create an aesthetics of continual transition, a simultaneous style of fusion and fission, where the unfixed multiplicity in his works remains manifest – though mysteriously unnamed and never fully known. Traversing spaces and stages, geographies and memories, lingual, cultural and political bounds, Ti Twazo Clarendon, utters many tongues and glimpses many vagrant visions, but the destination, the ideological nub or linguistic homing of such works never settles.

Fly little bird, over lands and seas, never cresting wave nor settling in trees: that is, meanings made through images are forever migratory, aerially born and fluctuating on the wing, resizing and reforming in the motion of the making of it. Home is, therefore, illusory; its boundaries and foundations unsettled; its perimeters forever expanding and contracting across the spaces of canvas, paper, sculpture, audio scores and the gallery itself. Although Robert goes a long way to bring it to us – from Haiti to the US to Europe then Haiti again – we get a sense that home, as it is for the migrant, as it is for the bird, is what you make it; home is what you carry; home is what you find nesting in your breast and smile. Home is your pronunciation of words, your intuitive parsing of phrases, spoken not across, but on the divides, in these transitionary places and phases where one thing is never just that: one. Ti Zwazo, Ti Ca, how are you, little bird? Where have you been?

For Robert, the image is never finished or stable. In ‘Tu Ca! Koté Ou Pralé, Ti Ca?’ (2022) layer upon layer of thick impasto lashes the central figure of a palm tree almost to the point of obscuration. Unfixed, almost uprooted, swaying in gusts of aquamarine blue, turquoise, marsh and olive greens, the tree barely withstands the clustering clots of paint – a climactic event all of its own. The legibility of the image – whether of a bird, a tree, a telephone box, a dog, or any other object or noun phrase – falters and stutters in the paint’s enunciation of it. You could say Robert buries his origins – or the originally inspiring objects and concepts with which he starts. Not so much like a dog burying a bone or a squirrel hiding an acorn, but as a bird hides an object within a new construction: a nest. Robert’s paintings – strange homes of estranged things – both nest primary images – the kernel from which his thought and practise springs – and are nests in themselves; complex matrixes, startling systems, careful constructions of disparate things. Just as a nest is to a home, and a home is to a body, so is Robert’s paintwork to the seed of thought and germ of his ideas. Palm trees twisting under the weight of their own being. ‘Tu Ca! Koté Ou Pralé, Ti Ca?’, though a more visually legible work, still harbours untold stories, unsung songs, alternate visions and versions that float then sink into the acrylic base upon which Robert paints. Re-emergence may only come through our own remaking of it; the travels of the eye, the ocular touch encouraged by the rise and fall of oil stacked like waves roaring over islets.

Nests in the tree, twigs of sentiment, the flotsam and jetsam that only the little bird knows how to treasure and spin, wherever he lands, into home, ‘Tu Ca! Koté Ou Pralé, Ti Ca?’ likewise gathers together an array of incongruent materials and (e)motions, concealing and revealing the original form, figure, fragment of land on which to chart our way into the work. ‘Where are you going?’ Robert’s title partly asks. Not, ‘where are you from?’ that most common of othering statements spoken to the newly landed bird whose feathers or call speaks of elsewhere.

‘Where are you going?’ as you move through the painting, learning to reconstruct then deconstruct a once central, now decentralised image. ‘Where are you going?’ as you search the nest of paint and nested thing therein, the disguised intention, the egg that has and has not hatched. ‘Where are you going?’ as you consider the unreachable destination, the return of a place that you’ve never been to before.

*

When I no longer hear their calls – or no longer recall them – the birds reappear in my drawings, a slither of wing, a beak, a claw, a hooked and crying memory from another side. Flying in, flying out of my sketchbooks in fluid lines of blue, they are never caught there; they are always ready to take off again.

I was once obsessed with their plumage, the mass of feathers that spoke to other birds, boasting of pride, allure, appeal – an action and attraction familiar to human animals too – not the skilful survival with which fur and skin and feathers are tasked. I would draw wings that spanned the whole page, paying meticulous attention to the patterns and striations of colour; bands of black, brown and white, and that oil-like sheen when the rain hits the ground in swirls and eddies of iridescence: mauve into turquoise into pink into gold.

I’ve never had an ornithologist’s eye. I cannot prize a scientific fact from a feathered filament or pin them down Darwin-style in a vitrine, admiring my own knowledge. There is magic in these wings; in the feathers, in the finger-like folds that hold a consciousness in flight and raise it up, close to the stars.

You can’t hold a feather up to the light the way a child holds a shell to their ear; it will not tell of lands visited, the trials that migrating from continent to continent, from North to South, East to West, will bring. Its fine pearlescent sheen is not a promise of a homecoming nor a loss of another’s home. Holding a feather up to the light will not unlock its voyage, however high you hold it aloft.

Asking how a bird sees itself, sees its feathers, sees its flights and “pit stops”, is like asking the nose what it thinks of the eye – who knows! It just is. But thrifty they are, these birds, with their Sunday best. The Elder Duck lines her nest with downy feathers plucked from her own breast. The Mallard sheds its glorious emerald plumes to resemble the brown feathered female in summer – a more common ‘eclipse’ in nature than many would care to admit (for are we not full of these artful transitions and transformations?). The Tufted Duck, the Scoter, the Pochard, the Pintail and Teal – indeed, all ducks and gulls have the aptly called ‘preen gland’ on their back which spreads a special oil across their feathered bodies, keeping them waterproof like the svelte suits of divers.

Divers of air and water, moving through mist, cloud and streams, rivers, lochs and seas; birds must gather and parse impressions quicker than the eye and nose and ear of man. And yet, when looking at their feathers, tributes to their movement, to their daring, to their mobile life around and above our heads (most of the time), I cannot gauge these impressions. I cannot trace this strand back to its nest, its travels, – the flailing palm tree battered by Atlantic winds – its sweeping of a globe burningly under threat.

Thoughts are not light as feathers, but neither are feathers as ‘light’ and skittish as one’s thoughts. They gather associations; they connect to a wider whole; they are a reminder of that which we stand to lose in the gaining of them.

Hold them up to the light, and they may, they may just echo this.

*

Ti Zwazo is on the fly again. Little bird spying land beyond sea. A gentle drift to carry him forwards. Europe-bound, though Haiti born and free. Two works of Robert’s repertoire dissolve the small bird’s hope for landed solidity and solid land in their own ways, transgressing the man-made barriers between here and there, water and earth, past and future. ‘With a Pinch of Salt’ (2022) has a sense of the dankly lit and distant infinite espied, at times, in Turner’s seascapes. A white net of canvas is flattened onto an acrylic mount, whilst blues, purples and blacks stream downwards like drizzle on a boat cabin window. Subdued colours drip across stuccos of white, and I see the little bird’s voyage, fighting through wind and rain, equidistant to the refracted vision behind and before him, watery scenes unfathomable closing in, no longer distinguishing between what came and what will come. All is indecipherably drenched and diffuse in blue, splashes of purple, trickles of pink, feathers coated in oil sheen, spilt liquid gold, clogging said downy breast, ocean-borne bodies and sights in a fight against life and death.

Look more closely between the rivulets of blue and mauve, and a black shape appears, apparitional though definitely there. This is no bird, but a small dog, a four-legged creature evanescent and fast evaporating under the strength and strips of dripping colour. This is Robert’s simultaneous removal and retrieval of the original image, the primary form which trips the painting practise into being; the artistic odyssey which then drifts and shifts to give us a body, a landscape, a collaboration and evolution of marks that no longer dog the scene with one single, solid, stable thing. No; it is but the abstract expression of a former gesture, a former figure that fugues into others, gesturing, figuring, outwards, in these gloriously fragmented fretworks of lines and states. A flight, a dive, a take-off and landing in one – or am I barking mad?

Despite its name, ‘Bell Atlantic’ (2022) brings us onto the terra firma, the inner city of New York, albeit one soaked in the torrential downpour moving in from the East Coast. As if from a dirty window we see the rain-washed cosmopolis. Drips of the same muted shades – tones of mauve, purple, lilac, Prussian and steel blues, or rather the artist’s own special blend of them – spill and cascade down a dense impasto (Auerbachian) background where lighter creams and whites swim and dance and glisten – sun and rain at once. Like ‘With a Pinch of Salt’, ‘Bell Atlantic’ obscures its initial image – that of a telephone box – in order to communicate a feeling that is entirely born of, but segues through, a damp windswept day in the city. The ghost of the telephone box, behind the impenetrable gloom and muddy murk of bluish black paint, appears towards the top of the work with the signage ‘phone’ and some digits coated in a yellowing moon of paste. Numbers glow and gleam under a gel-like covering all of Robert’s own invention (and again, a medium he won’t divulge); type we cannot dial or recall coherently. Type and phrases we cannot say out loud.

‘Bell Atlantic’ plays with us then. It plays with disclosure and closeness, proximity and distance, densities and intensities of thought and feelings fleetingly felt in the creation of the work and the recreation of it for ourselves. Losing the map to this particular site of communication, to this cityscape and urban happening, Robert beckons to us from an unknown space – perhaps from a curb over there or a window over here or from a phone box in the centre of it all, downtown, where the rain won’t stop and the avenue looks frighteningly alive. Perhaps from a window sill or telegraph pole, where only a certain winged creature may survey the gutter and the heavens at once; in one fell swoop.

Little bird, calling out, what do you see? Ti Zwazo, ti ca, flying over streets and trees. Tastes of brackish water, salt breeze seasoning rotten leaves, I have left my ocean dwelling for the rain-tossed forest of concrete; this rained on, forsaken city.

Andy Robert, ‘Atlantic Bell’ (2022) Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

*

What if a nest is not a place of safety, but a trap, a lure, a place of woe?

Birds of the metropolis – the sparrow, pigeon, blackbird and crow – build lives up high – and occasionally down below, on ponds canopied with duckweed and algae, embellished with plastic bags and rusting cans. The Moorhen, Swan and Coot create circular mounds upon which to lay and sit on their eggs. Twigs, broken branches, leaves, feathers, blades of grass and other vegetation are woven with an inherent ingenuity and intricacy to form flattened baskets of the most impressive kind. Whether ‘his eye is on the sparrow,’ they spin and toil without complaint.

I have watched a moorhen slowly build her nest in the most vulnerable place: the middle of a river. She will find a disused fountain spray, a floating log, a limb of a tree forlornly tipped into the watery surface, some fallen debris, moss covered and river soaked; she will find these locations and build, architect and engineer and labourer in one. She will build, after foraging for discarded remnants from the “natural” and “synthetic” worlds: twig into leaf, leaf over grass, grass into plastic, plastic over feather and so on and so forth, until a temporary home, water-tight and water-bearing, holds her and her deepest treasures. Holds her future hopes.

We write with mixed components, weaving words worn of former meanings now glazed with newer ones, again and again. We build with words from other cultures passed onto us from other events, other times, other places, other narratives. Ti Ca, Ti Zwazo, Little Bird. We speak, we call to each other from afar, our tongues often ignorant of the history unpronounced behind that which is uttered. Ignorant of the gulf these words must bridge. Ignorant to the original pronunciation of a word, its etymology, its original home. Little Bird, Ti Zwazo, where are you going? Look how far you’ve come.

We speak, we write, we paint with things discarded and retrieved; things rediscovered, things reconceived. Over and into, we spin our nests, our containers, our life’s works, our homes, in which to keep our treasures; in which to keep our egg-shaped hearts.

*

Despite its watery title and feel, ‘Bell Atlantic’ has something of the nest about it. Repurposing timber from a roadside construction site, Robert hangs his canvas jaggedly on broken wood, an image framed by an expositional space-cum-object that no longer has the same function or significance it would in its usual metropolitan habitat. White and vermillion bars that would formerly warn and ward off, now alert us to the draped world opening out on its battered wooden surface. Substrates of wood belie surrounding surfaces of paint, their respective subtexts colliding. Drift wood has now been turned into a literal and metaphorical window – another kind of liminal and heterogeneously crafted container – through which we glimpse and hear the city thunder into view above the wet weather’s continual noise. I still see the sea; I see the vapour and mists and electric lights shine through sheets of rain made worse and grey from the harshest conditions known to the Atlantic; I still see Robert’s other water-inspired paintings conjuring myth and history and creativity and the hard-won, hardily salvaged knowledge known only to those who form the Black Atlantic; I see the waters carrying indistinct forms, migrating mirages of things once known now no longer known to us, submerged, sinking, settling like sediment along the deep. I see the liquid sense of being and seeing that comes through painting and mark making, the only true conduit to bring us living water; and I see those waters gently parting to unveil the first image, the telephone box, another sign and signifying thing behind the paint’s densely thick significance.

Still, I see the driftwood, reclaimed, refurnished, repositioned, rehung, turning out the entire artwork to confuse the manifold dimensions, elements, seasons and reasonings lying therein. We’re not lost at sea, in our boat-like nests, any more, little bird. We’re lost and alone on the rain-slick streets of the city, clinging to any nest, branch, twig we can find. Ti Zwazo, ti ca, little one, kote nou ye, no longer where are we going, but where are we?

*

Downstairs, we find ourselves, the curator, H and I. We are listening to a recording of birdsong pouring through the wooden door of the gallery’s front-facing room. We are standing almost on the exact spot where Robert himself painted a luminous work which now towers over us. Pinned to a white wooden door, Robert’s latest painting, ‘Asylum’ (2022), is a fit of rapid white, grey and black marks tumbling and writhing around on white linen pinned to derelict door. I’m wary of reading too much into the title: its clinical whites hide the beginnings of another figure (another creature) in black that I can’t fully make out, and I don’t want the title to straitjacket this vision into something it’s not. Then again, the title may direct us down an alternate corridor; an antithetical one about notions of home, belonging, seeking safety and safe passage. Following the birdsong, follow its early call, and you may just find your way home again.

This reading chimes well with the painting/sculpture installed to the left of the actual door emitting the high pitched chirrups of birds. ‘House Fly’ is Robert’s cast iron radiator, reclaimed and releasing, not air nor heat, but the recorded gurgle often heard with such systems of heating. No longer in the Michael Werner Gallery, we are now in a newly converted space reminiscent of the artist’s own home and homing experience. Nesting here, for his temporary residency and first European exhibition, Robert re-enacts the bird’s instinct to build with surrounding and newly found materials – a discarded wooden door from London, a radiator from NYC – to approximate a sense of home, to re-establish the familiar, to reorient himself in the unknown. We hear birdsong as he would in his city apartment; we hear the cast iron radiator crank into action (conducting more than heat) as he would too. We’re offered a portal, a doorway, an opening into a select aspect of his living, his routine, the guiding audio visuals that translate as well as transverse his domain. Going beyond his room, his body, into this room and our bodies, the little bird carries us something from afar, an olive branch, a trinket or token of what exists over there, though we’ve never seen nor visited it before. Like so many birds that come from “foreign” lands and seas, he leaves and gives more than he’s taken.

And so, decontextualizing things, Robert allows us to re-contextualise and reweave them into the nest of our own experiences, our own sense of comfort, security, the known and unknown. A tribute to his home or homemaking, to being from and of both “here” and “there”, Robert destabilises all former associations and asks us to reconstruct the nest, the home, the painting, the experience, and indeed, the self, with him.

The last room, however, is, undeniably, him and his. Little bird comes full circle from Haiti to NYC to London and back again Birdsong and heat turn into a heartbeat just as palpably deep and full and lyrical as those former sounds and the visions they attend. In his incredible work, ‘Nèg Nago soti Etazini: 255 East 25th Street How frightening is it to see oneself dissolve; transmuted’ (2022), repeated automatic marks make up an auto-portrait of Robert himself. Emerging from a network of replicated lines, Robert’s spectacular spectre of a face hovers at the base of what looks like an equally spectral habitation of some kind: a high-rise building, an incomplete tower, a deserted construction site or ghost town. The nowhere and everywhere, the America and Haiti, of a migrating bird. Fusing Haitian Creole with American English in his title, Robert again alights on being a composite of both places and cultures (yet never truly being fully ‘of’ or accepted ‘by’ either one), so that his collection of drawn and painted marks implies the respective mark these two supposedly opposing nations and cultures have made on him. Pulsing behind the portrait is an audio recording of his own heart; it beats periodically, when the audio score of a woman singing a nursery rhyme – Little Bird, Ti Zwazo – cuts out.

Here, again, home is where you choose to remake it. Home is the body in which we store our most secret selves; it is also the spatialized and architectonic body of a flat imported across land and sea; it is the chronos of memory and the time of the clock; it is the singing of a loved one, the ringing of the phone, the cries and caws of birdsong beyond your window, the continual beating heart. Home and the self that we depend upon to reiterate and narrate it, is here – and it is also over there; it is ‘diffused’ and ‘transmuted’, remixed and repurposed for those most vulnerable, those whose diffuseness and difference will always be seen. Those who are never stationary, but on the fly, seeking homes, nests, havens in other lands, across other seas, sometimes afar, sometimes near, but restlessly seeking, searching, seafaring and flying to new destinations, new climes. Bye bye, little bird, where are you going now? Why do you leave? Ti Zwazo Clarendon, Ti Zwazo London, Ti Zwazo, fly away, no; speak to me of Haiti again.

Andy Robert, “Nèg Nago soti Etazini: 255 East 25th Street: How frightening it is to see oneself dissolve; transmuted”, 2022, Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles.

*

The birds have returned again, returning me to my own sense of being neither here nor there; of being in London and Cyprus at once; of being a small child in an adult’s body with words yet to unfurl on my tongue, visions yet to spring from my fingers.

Two pigeons coo and purr to each other, two pigeons talk in a language not my own, preening on the roof of my attic room. The rain has stopped. The scaffold taken down. Only feathers and twigs amass on faded slates and moss-strewn tiles, across a mass of tangled cables and wires. The pigeons are home, for now; they are at home on a house not their own – nor mine either. They will nest there for a few months, until they and they’re surviving brood leave, fly off, perhaps recoup again, elsewhere, in another land, across another sea.

In my room, my nest, my unowned temporary crowded home, disparate things – books, clothes, blankets, postcards, posters, the feathers and stuffing of my life – assemble and reassemble themselves in the changing light of day, precious to me but no one else. In my sketchbook, I draw a curved line, perhaps the start of a wing, a face, a dog or a door. Little bird, look how far we’ve come; little bird, look how far we’ll go. On that page, in those lines, a heartbeat begins.

*

Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou is a writer, the founding editor-in-chief and general arts editor of Lucy Writers, and is currently writing up her PhD in English Literature (and Visual Material Culture) at UCL. She regularly writes on visual art, dance and literature for magazines such as The London Magazine, The Arts Desk, The White Review, Plinth UK, Burlington Contemporary, review 31, Club des Femmes, The Asymptote Journal, The Double Negative and many others. From 2022-2023, Hannah will be managing an Arts Council England-funded project for emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds, titled What the Water Gave Us, in collaboration with The Ruppin Agency and Writers’ Studio. She is also working on a hybrid work of creative non-fiction about women artists and drawing. Read her work https://linktr.ee/hhgsparkles Follow her on Twitter @hhgsparkles and Instagram @hannahhg25

*

The moral right of the author has been asserted. However, the Hythe is an open-access journal and we welcome the use of all materials on it for educational and creative workshop purposes.